Let’s begin with religion…

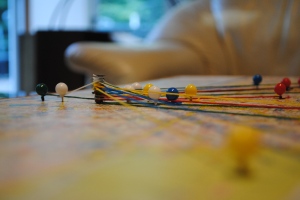

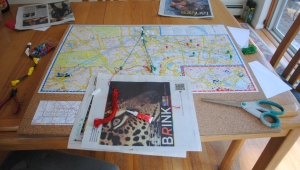

The red pins on the map are for religious buildings I visited. As I said before, some of the places I visited that would’ve fallen under certain categories are not shown, for they are not on my map of Central London. Some people suggested that I guesstimate where the pins would fall and plot them anyway, but I decided against that. This map is the only map that I personally used throughout my entire trip to London. It’s torn and has some highlighter stains on it (as did a pair of my shorts I had to get rid of); the places not shown, such as Highgate Cemetery, were places that I relied almost solely on the directions my professors provided the class with. I didn’t use a physical map to get to those places, so I’ve chosen not to physically map them.

There are four red pins on the board: Westminster Abbey, St. Mary Le Bowe, St. Paul’s Cathedral, and St. Clement Danes. It was hard to find some of the churches on the map because there are so many churches in London! Jeez! Red crosses can be found every few centimeters on the map. This study abroad session has shown me that religion plays many roles on Englishness. I’m not a very religious person myself; yes, I believe in a higher power and try to live a good life and pray sometimes, but organized, institutionalized religion is not exactly governing my life. While in London, I noticed how people, including myself, were affected by the inescapable presence of religion due to the abundance of churches on every corner.

My class went on a church tour, visiting all of the churches mentioned in The London Scene by Virginia Woolf. St. Paul’s was the first stop on our tour, where some very noticeable things happened. Michel Foucault said in an interview that, in order to understand an architectural space, one must consider “the effective practice of freedom by people, the practice of social relations, and the spatial distributions in which they find themselves. If they are separated, they become impossible to understand. Each can only be understood through the other.” While visiting the churches, I kept an eye out for these factors.

“one must take him – his mentality, his attitude – into account as well as his projects, in order to understand a certain number of the techniques of power that are invested in architecture

The actual cathedral of St. Paul’s can be seen from miles away; the architecture is breathtakingly enormous and asserts the power of the church for all to see. How everyone was occupying the space around the building was equally as fascinating as the architecture itself. People on the steps of St. Paul’s were eating lunch in business suits, congregated in groups or taking pictures, students (both elementary and college level) and learning about the history of the cathedral; everyone was casual and seemed to move relatively freely about the stairs. What was interesting was how everyone was talking; the noise level was super quiet and respectful, especially for the amount of people around. Though from a distance it might’ve appeared that everyone outside St. Paul’s was oblivious to it, once you took a closer look (and listen) the presence is felt by all. People control their voices and keep them down to a quiet, meditative level that is unobtrusive to those surrounding. Everyone is a bit more respectful of each other here than in other places I visited.

St. Mary Le Bowe’s and St. Clement Dane’s were quite different from St. Paul’s; the churches were much smaller and this affected how people occupied the space. Mary Le Bowe’s has a cafe in the basement, which seemed to receive more attention than the church itself. Clement Dane’s was located in the middle of the road and the inside is no longer open to the public. The smaller sized churches were easily forgotten about; one can argue that this is because of their size and where they are in the city. Mary Le Bowe’s might be using the cafe to try to get more people into the church, while Clement Dane’s simply faded away. Either way, the people occupying the space around these two churches were almost completely unaware of their presence. Mary Le Bowe’s is a tiny little church wedged into a street; Clement Dane’s is in the middle of a busy highway and out of the way. These factors definitely contribute to the fact that they are less frequented by the public.

St. Mary Le Bowe’s and St. Clement Dane’s were quite different from St. Paul’s; the churches were much smaller and this affected how people occupied the space. Mary Le Bowe’s has a cafe in the basement, which seemed to receive more attention than the church itself. Clement Dane’s was located in the middle of the road and the inside is no longer open to the public. The smaller sized churches were easily forgotten about; one can argue that this is because of their size and where they are in the city. Mary Le Bowe’s might be using the cafe to try to get more people into the church, while Clement Dane’s simply faded away. Either way, the people occupying the space around these two churches were almost completely unaware of their presence. Mary Le Bowe’s is a tiny little church wedged into a street; Clement Dane’s is in the middle of a busy highway and out of the way. These factors definitely contribute to the fact that they are less frequented by the public.

I won’t go into detail about Westminster Abbey (there’s a whole other blog post about that one- check it out!) but even though some of these buildings have fallen out of use to the public, they still contribute to the overwhelming presence of Christianity in London. These buildings perpetuate the dominance that Christianity has over Englishness.